|

Felix

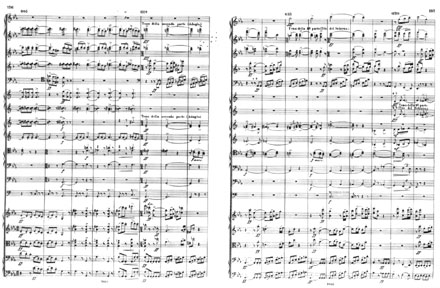

Draeseke's "Symphonia Tragica" Part IV Alan H. KrueckThe Third Symphony of Draeseke was composed in 1886, contemporary with the first version of Bruckner's Eighth Symphony, a work which has many obvious features in common with Draeseke's work. Yet even Bruckner continues to hold to the struggle-to-victory ideal which had been the heritage of Beethoven's symphonic thinking. This detracts in no way from Bruckner's titanic masterpiece but it should give the public reasonable cause to reconsider Draeseke and credit him with the originality of musical thought and execution which seem justifiably his in the Symphonia Tragica, for he takes his concept of the tragic one formal step further than any other symphonist to the time, promoting not only cyclical development among the movements and providing a contrapuntal summary of themes in his finale, but actually returns the symphony's introduction, with all its tragic foreboding, as a coda of tranquil repose at the work's conclusion. The resolution of tragic conflict in the symphony's home key of C major is but a temporal pause and allows one to understand the reason for the octave dominant G’s of the very beginning: the entire struggle has been to accept rather than overcome, necessary repose before the tragic resumes once again, for true tragedy is never fully resolved: synthesis will produce thesis to be countered by antithesis and the Hegelian cycle will renew itself. Through this Draeseke may have come to his conclusions concerning the design of his symphony in consideration of Wagner's Ring, for the Ring is a cycle of four operas (paralleling the four movements of a symphony) created from a view of humanity’s tragic destiny (a la Schopenhauer) and employing a leitmotivic system of characteristic and symbolic intervals which result in thematic relationships throughout and leads to even a contrapuntal integration of themes in a final summary at the end of Götterdämmerung. In this respect the presence of Wagner's Geist seems undeniably present in Draeseke's formative thought, as a stimulant to both philosophical and musical considerations. Draeseke retains his unique musical personality but, like most composers after Wagner, Wagner's achievement in the Ring, particularly its reflection of concepts of Hegel and Schopenhauer, become an integrated part of a general Weltanschauung concerning the human spirit and belief that only in the ideal can one come to terms with the tragic conflicts of reality - certainly apparent in the Ring. Just as we can imagine the low E-flat of Rheingold beginning anew the generation of tragedy after the D-flat transfiguration of struggle in the final pages of Götterdämmerung, so also can we entertain Draeseke's purely instrumental effort as an acknowledgment of Wagner's spirit. Yet it is not Wagner alone who should be given consideration here, for much of what Draeseke publicly stated about the symphony has to do with Beethoven as well and there is no doubt that Draeseke saw himself, the contemporary of Wagner and heir to Beethoven, somewhere in the middle. This gives one pause to consider the relationship of the movements of the Tragica in a dual aspect. First, in relation to Wagner, one notices that the first and third movements end joyously, as do the first and third operas of the Ring, Das Rheingold and Siegfried while the second and fourth movements end quietly, as do the second and fourth operas of the Ring, Die Walküre and Die Götterdämmerung. In the first and third movements of the symphony one encounters quite obvious classical, in the sense of standard, formal developmental features, whereas the second and fourth movements seem to arise from much expanded and freer notions of design. In regard to this Draeseke may have been consciously setting up a polarity between the Beethovenian and Wagnerian in his considerations, a polarity which certainly can be observed in much of Bruckner, particularly in the Eighth Symphony, even though its scherzo is placed second. Of

particular importance in crediting Draeseke's originality in the Symphonia

Tragica is the application of the tritone clash C-F# (or

its enharmonic manifestation) Although Draeseke's Symphonia Tragica had a number of major proponents during the composer's lifetime in figures like von Bülow, Nikisch, and Schuch, the work made little headway outside Germany and it seems even today to await a public performance in the United States. Be that as it may, the generation of German conductors which came to the fore after the First World War grew ever more distant from Draeseke and his accomplishments. During the National Socialist era, among the conductors who remained in Germany, those in the forefront (Furtwängler, Knappertsbusch, etc.) remained distant from the movement to position Draeseke among his already established contemporaries. Most conductors endorsed the promotion of composers like Bruckner and Reger during the Third Reich, at least in regard to the deceased. Karl Böhm, Carl Schuricht, and Hans von Benda supposedly conducted the Symphonia Tragica at the time and less well known conductors (as is the case today) interested themselves, whether for political or genuine musical reasons, in Draeseke's output. The only

recording [xv] of

the Symphonia Tragica was done in 1942 (in remarkable

sound for the It was not until the founding of the International Draeseke Society in 1986 in Speyer, Germany, that recordings began to appear but, as of this writing, no orchestral music by Draeseke has been released on commercial recordings[xv]. The reasons for this are mystifying on the one hand, since Draeseke is not a composer whose style is in the least bit forbidding, but his intellectual tenacity demands more than a single performance encounter of any given work, a consideration not required by many a well-crafted and tunefully superficial symphony (for example) by worthy contemporaries. Hermann Kretzschmar[xvi] warned specifically of the "harte Zuege" (tough qualities) in Draeseke's symphonies, but he also extolled the rich rewards brought with further acquaintance. Less mystifying is the fact that Draeseke's symphonies- and in particular the Tragica - deserve and require first class conductors and orchestras for success in performance: Bruckner and Reger (not to mention Mahler and Strauss) have almost a century of performance tradition for their orchestral works, and most of those works have long been accessible through easily obtainable scores and commercial recordings. Not so in the case of Draeseke, who remains possibly the least known major German composer of the last century, perhaps the most tragic fact concerning the composer of the Symphonia Tragica. In conclusion one should return to the title of this paper and give final answer to the question: "Felix Draeseke’s 'Symphonia Tragica': Wagnerian 'Geist' or Symphonic ‘Zeitgeist’?" It should be fairly obvious from the commentary on Draeseke's personal relationship with Wagner, his association and endorsement of "New German" ideals, his shared philosophical and literary interests and the absorption into his uniquely personal musical style of certain aspects of Wagnerian idiom (harmony, orchestration, developmental techniques) and especially in the Symphonia Tragica, ideas paralleling concepts from Wagner's Ring des Nibelungen, that Wagner's Geist or "spirit" is very much in evidence. In regard to symphonic Zeitgeist - the German as term defined by Hegel - one must also admit that the Symphonia Tragica is very much in the spirit of its time, especially in regard to the more advanced symphonic thinkers at the time, those who were producing symphonies based on cyclic elements. It is astonishing to consider that within three years of Draeseke's composition either way, symphonic repertoire was enriched by such works as Bruckner's Eighth Symphony, the Third Symphony of Saint-Saens, the D minor Symphony of Cesar Franck, the Seventh Symphony of Dvorak and the Fifth Symphony of Tchaikovsky, each of them showing some type of cyclical formal principle. In this regard Draeseke's symphony is in the tradition of the prevailing symphonic Zeitgeist of the period; but there is also the consideration that the contemporaries mentioned, were also indebted in one way or another to Wagnerian influences. One might even say Wagnerian Geist is a major part of the symphonic Zeitgeist of the time and that symphonists like those mentioned above were offering their own incidents of synthesis to the interaction of then current musical practices. [xv] This was the situation at the time this paper was originally presented in 1996. Since that time, several digital recordings of Draeseke's orchestral and chamber music have appeared, including two of the Symphonia Tragica and all four of Draeseke's symphonies are now available on CD; see the Discography for details. [xvi] Kretzschmar: Führer durch den Konzertsaal, p.720. With the exception of the quotation from Richard Wagner's My Life, all quotations from other German sources are translations from the original by the author of this article, Alan H. Krueck and, as such, are to be given appropriate reference citation. © Copyright

by Alan

H. Krueck: 1996, 2004 |

|

[Home] [About IDG] [Discography] [Links] [Compositions] [Essays] [Listen] |

||

throughout the work. Admittedly it

poses no path breaking harmonic procedures since its use really

stems from fairly standard harmonic cadence. But the fact that

it is used symbolically in the music places Draeseke ahead of many

who have been credited with far greater historical significance

because of its use (one thinks primarily of Stravinsky (Petrouchka)

and Britten (War Requiem) in the 20th century). By the beginning

of the 20th century the tritone had become a prominent feature

in much harmonic thinking characterized as impressionistic and

it seems quite apparent in turn of the century symphonies by such

diverse composers as Scriabin and d'Indy. Indeed, d'Indy's Symphony

no. 2 in B flat major - surely one of the greatest French symphonies

- almost parallels Draeseke's Third Symphony, except that d'Indy

employs the tritone for thematic material which is subsequently

transformed: it is also the tritone which harmonically underpins

the integration of themes in the final chorale summary at the end

of d'Indy's imposing work.

throughout the work. Admittedly it

poses no path breaking harmonic procedures since its use really

stems from fairly standard harmonic cadence. But the fact that

it is used symbolically in the music places Draeseke ahead of many

who have been credited with far greater historical significance

because of its use (one thinks primarily of Stravinsky (Petrouchka)

and Britten (War Requiem) in the 20th century). By the beginning

of the 20th century the tritone had become a prominent feature

in much harmonic thinking characterized as impressionistic and

it seems quite apparent in turn of the century symphonies by such

diverse composers as Scriabin and d'Indy. Indeed, d'Indy's Symphony

no. 2 in B flat major - surely one of the greatest French symphonies

- almost parallels Draeseke's Third Symphony, except that d'Indy

employs the tritone for thematic material which is subsequently

transformed: it is also the tritone which harmonically underpins

the integration of themes in the final chorale summary at the end

of d'Indy's imposing work.

period)

by the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra under

period)

by the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra under